It’s probably the first big story I can remember where UGC has become a real factor in reporting, I think before that the UGC Hub was a department which was a bit unclear how you would best use them...But with Syria we were so exposed out there with not many people we had to use something. And they would become integral to reporting basically because they were only the source of getting some idea of what was happening.[1]

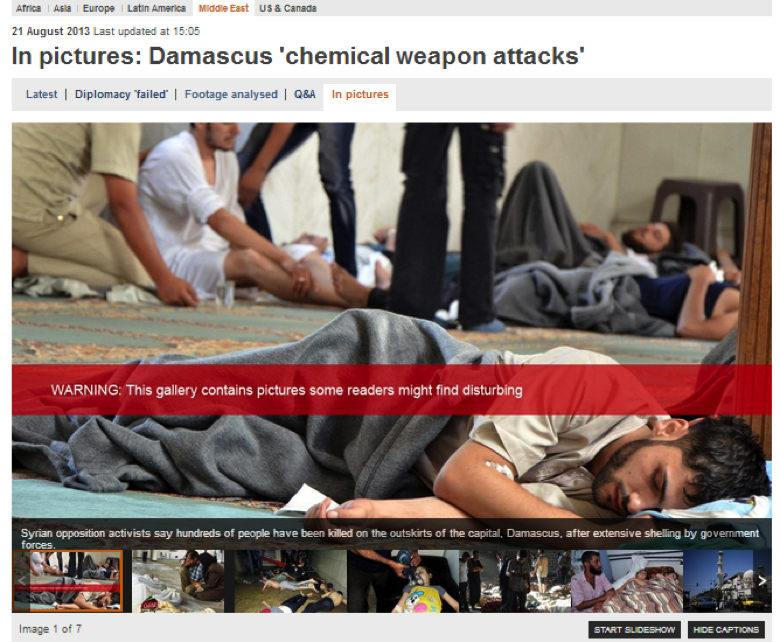

It’s just after two o`clock on the morning of 21 August 2013 and in BBC Broadcasting House in London, journalists at the User Generated Content (UGC) Hub are pouring over YouTube footage. Over the next few hours, a team of BBC producers will sift through dozens of video clips as the newsroom reacts to reports across social media and from traditional media outlets that a chemical attack has taken place in the suburbs of Damascus. There are no BBC "boots on the ground," so it’s a case of putting together pieces of the jigsaw based on this footage and reports from wire services and local outlets. Welcome to the modern newsroom where producers relying on grassroots media and activists, in what might otherwise be a journalistic vacuum.

The way BBC staff access content has changed since the start of the Arab Spring, but particularly since things kicked off in Syria. From the first protests in Der’aa in March 2011 onwards, for the BBC to get an accurate portrayal of what is going on in the country has at best been challenging, at worse not possible.

The night of the chemical attacks there are no BBC journalists near the scene, though Ian Pannell is in the north of Syria. Therefore, as they have done many times before, BBC producers have turn to social media and their established contacts–the ones they can still reach–to cross determine what is going on. The end result is a mix of UGC clips with correspondent inserts across many different news reports online and on television.

This is certainly an example of the BBC engaging with its potential audience to create content. This is less traditional frontline reporting and more akin to newsgathering in the form a conversation, something Dan Gillmor [2] believes is transforming the way we create and react to the news.

This paper explored the way that journalists’ roles at the BBC have changed since the start of what the corporation calls the "Syria conflict." The study also looks at how BBC staff engage with what they describe as "media activists" on the ground in Syria. It draws on extensive interviews with BBC staff and periods of newsroom observation at the BBC UGC Hub, BBC World, and BBC Arabic.[3]

As background to this development, it’s important to highlight that at the start of the Arab Spring, BBC staff would get video content sent directly to them. Findings based on interviews and newsroom observations carried out over from June 2013 onwards suggest that role of the BBC UGC producer has evolved to become one more likely to involve analyzing content from online resources such as a YouTube channels and material linked to via Twitter feeds. In particular, groups such as the Local Coordinating Committees (LCC), across Syria, have become a crucial news source.

[Logo of the LCCs circulated online]

Set up in March 2011, the LCCs consist of a network of activist groups on the ground that organize and report on what is happening in the country on a daily basis. They are not impartial and historically were involved in organizing protests in connection with what they refer to as "the uprisings." As of February 2012, the network had fourteen local committees, which look after different geographical locations, and come under one umbrella group.

BBC staff interviewed for this research claim that the LCCs have become more organized as the conflict has gone on. As well as their own website which has content in English, the LCCs have set up several Facebook pages where they have started to upload content from different rebel groups, providing context on what they believe the video footage shows with a description in both Arabic and English. BBC journalists spoke of certain activist groups becoming "trusted sources" for the BBC over time, and if their information and content proved to be reliable, it was more likely to be used.

BBC staff didn’t just approach activists groups, but also individuals who gave good information over time. Their details would be put together in a comprehensive contact list which staff, particularly those working in television would refer back to and update regularly. This meant certain voices would be put on air again and again and confidence in using these people would build up over time. For example, a Syrian activist known as Manhal Abo Baker was used regularly from 2011 throughout 2012, both on BBC News and also other outlets.

Another key contact was Homs based activist Abu Rami–who appeared on BBC World News TV several times including in June 2012. He also featured in BBC online articles and was widely quotes on by other news outlets.

In terms of covering Syria, BBC staff acknowledged that in the first months of the conflict, while they did try to get what they described as "pro-regime" voices on air, or at the very least supporters of Bashar Al-Assad, these became thin on the ground as weeks went on.

I cannot remember how many countless times I have tried to get the Syrian foreign ministry or a government spokesman on the program. Many, many times, but often, in fact I don’t think we’ve ever, maybe once or twice in the earlier days we got a government advisor on, but often when you approach people who are pro-government online they respond and say, ‘I’m not coming on, cos you’re biased.[4]

It very difficult to find people, and the language barrier too, to find people in Syria who are pro-government and can speak English has been almost impossible.[5]

The obvious danger of getting activists, some of whom may be affiliated to LCCs or other organizations, is that their viewpoint may be skewed.

This raises interesting questions about how television outlets can achieve balance when one side of an uprising is unwilling or unable to be heard. Concerns about whether the BBC has said enough about the different components of the Syrian opposition and political options should Bashar Ad-Assad be displaced were highlighted in an impartiality report on the Arab Spring by Edward Mortimer in June 2012, which was subsequently followed up in August 2013 to detail new developments at the BBC.

When "opposition voices" were the only ones BBC journalists could get on air, producers said they tried to challenge their viewpoints, aware that these individuals would be posting a certain narrative and might exaggerate stories. They were also aware that within Syria, there were many different fragmented groups, and the all-encapsulating term "opposition voices" may not be entirely accurate.

Overall, journalists said they experienced a "steep learning curve" in terms of developing skills to process the high volume of UGC being uploaded to online sites, as well as having to become much more tech savvy, using social media to find people willing to speak about what was happening inside Syria. While some staff had experience with UGC from other Arab Spring countries such as Egypt, this footage was frequently used to complement journalists’ work on the ground. Learning how to deal with UGC from Syria was largely done "on the job," so as to meet demands for quick turnaround of footage so it could be used by BBC outlets.

I was already familiar with ways to find people that aren’t immediately obvious to find because I was already doing this with countries like Libya and Egypt. So when things started happening in Syria I already had an idea of how to get hold of these people...Nobody taught me how to do that...I was sort of following my own path if you know what I mean. So when we picked up on that, the sort of Skype/Twitter aspects, that’s something I guess couldn’t have been done in previous wars, five years before, because it wasn’t there.[6]

The move to use this content is indicative of a changing media ecology. Journalists are not the only people who capture the news, and citizen content can help news organizations illustrate events taking place where journalists have not got access or are unable to get to the scene on time. Stuart Allan refers to the concept of "accidental journalists" and those who engage in "citizen witnessing,"[7] citing the blogger Sohaib Athar who inadvertently live tweeted the raid in which of Osama Bin Laden was killed in Abbottabad as the perfect example . In some ways this label seems more appropriate when talking about content from Syria that the BBC process compared to the very broad term "citizen journalism," given that so many different scholars have debated what exactly citizen journalism is and how it should be conceptualized.[8]

Jay Rosen says that citizen journalism happens “when the people formerly known as the audience use the press tools in their possession to inform one another.”

A person capturing footage of barrel bombings in Damascus is undoubtedly an eyewitness and the content is UGC, but are they playing the role of journalist, or are they just a pair of eyes? And if the content is picked up by the BBC and framed in a different way from what the eyewitness intended, does that then change what the content should be classified as? Much research has already considered the debate on categorizing individuals as well as content, [9,10,11] and this paper doesn’t aim to provide answers, but it’s important that people interested in how UGC is used to be aware of the discussions and debates around it.

In the case of Syria, the press tools which Rosen describes are usually mobile phones to used film footage, though some BBC staff reported viewing clips that featured portable BGAN–Broadband Global Area Network–terminals often used by professional journalists, in shot. Henry Jenkins would describe these developments as a form of media convergence, and through the use of smartphones on the ground activists and other eyewitnesses are able to become involved in a participatory culture which sees their content becoming part of the story.[12] This content may end up appearing across many platforms and outlets, including the BBC on TV, radio, and online.

While some newsroom staff interviewed for this research considered the content to be ‘just another news source, others felt their role had changed–they reported using different skills, consulting different sources and managing this content in a very different way to traditional sources. One staff member said her job was no longer clear cut - she was "part detective, part librarian," as well as a journalist.

Twitter and Facebook are massive now in a way they weren’t when I started on our program…So that’s a resource that we have now, and it means, because it is publicly searchable you can go out and find stuff that happens to be out there rather than it having to come to us.[13]

As the role of the UGC Hub has evolved, the way its journalists go about checking content has “become much more forensic,”[14] and the BBC has introduced social media guidelines for staff. Alex Murray, a BBC broadcast journalist, also documented a "UGC checklist" detailing the processes journalists should go through in a bid to determine if content is what it claims to be.

UGC Hub staff also acknowledge the benefits of drawing on the expertise of their colleagues in BBC Arabic and BBC Monitoring, with whom they frequently liaise to analyze accents and language, which has played a massive part in verifying UGC. Now anything from people’s clothing, to significant buildings, the weather and varieties of flowers are used to deduce whether material shows what it claims to. In addition, a member of BBC Arabic staff is now permanently based within the UGC Hub.

Partially as a result of newsroom changes at the BBC, whereby most news staff are now based at New Broadcasting House in London, the Live and Social producer role was established. This sees a UGC staff member sit alongside the newsgathering team each day, meaning they are in a position to react to any breaking news, as well as carrying out the traditional sourcing of voices and of content. The producer will also attend editorial meetings, be a point of contact to take requests from individual programs for UGC, and highlight to editors what material is available, with any caveats such as warnings about its origins.

Another interesting development during the lifetime of the Arab Spring is that the type of footage submitted and encountered by the BBC has altered. Rather than a long clip, it is now common to see sequences edited together, or for it to include "signposting" such as dates or filming of key landmarks thought to be an attempt to make content easier to verify. This finding echoes those from other research on the BBC[15]. While this could be an example of content creators becoming more sophisticated and recognizing the needs of mainstream media outlets, there is also evidence of people trying to push a certain narrative using video. For example, interviewees reported activists recycling old footage, framing it in certain ways, upping the number of people attending rallies and eyewitnesses exaggerating death tolls

So they use all the tricks that you get elsewhere. They used donuting (i.e. shooting around a subject)– so in Hama you would see a big protest round the clock tower and then you’d find a wider shot of it – and it was a big protest around the clock tower, but it wasn’t a big protest in the square...There was also one example as well of duplicating sounds on audio. I think one of the picture editors spotted that exactly the same gunshot happened repeatedly, because it was the same sound wave...Or you’ll get a piece of footage where the original was done without commentary, but they had added in their own commentary about where it was and when it was at a later date.[16]

Throughout all participant observation, and also from a production perspective, it became very clear that being accurate and using UGC appropriately is of paramount importance to BBC staff. They take verification of content very seriously–even UGC from established agencies like EVN, AP and Storyful–a news wire services whose main role is to look at and verify social media content–are subject to the same checks as a piece of footage uploaded to YouTube.

On one occasion, an interviewee explained that "[Syria] was a big turning point I think for UGC and now their synonymous with any place or story which is out of our reach.”[17] Drawing on the experience of these producers we see how social media helps the BBC cover the Syria conflict, and the ways that journalists have adapted to deal with UGC in new ways. UGC and social media are now key tools in the newsgathering process, and this content is being used as a key news source when BBC correspondents cannot get to the story. In the case of a major event such as the chemical attacks on August 21 2013, this footage is the only way to depict events happening in the country.

The danger of having to rely on this content is obvious, and the BBC seems to have taken these risks on board. The corporation has reframed some of its guidelines on using social media as a result. The content in many cases enhances coverage on what is a challenging topic to cover, but there is always danger of portraying just one side in what is an increasingly fragmented conflict, where there is no long a pro and opposition side, but many different narratives in between.

Three years on from the beginning of events in Syria, the way the BBC deals with UGC seems to have altered. BBC producers are more likely to go to online sites such as YouTube and Facebook to find content from Syria, rather than have it sent into them. They will follow set procedures for verification and new checks have been put in place when considering whether this content can be put to air.

Moreover, new coping strategies have been introduced which will allow the UGC Hub to cover the story on a day to day basis seems, such as the creation of the previous mentioned Live and Social producer role, and the embedding of a BBC Arabic producer within the UGC Hub try overcome language barriers when process Syria video footage.

As the violence in Syria continues, the amount of UGC being generated continues to grow. Looking to the future, how BBC journalists use and process this content could have implications in terms of further developing newsroom policy at the BBC, and could lead to changes in the journalistic guidelines which referenced by BBC News on a regular basis. For the first time in 2011, these guidelines included a specific section on social media, indicating a change in how the organization perceives this content, and perhaps also, validating UGC in terms of its value as a news source when the BBC are trying to cover events in countries that would otherwise be a journalistic black hole.

--------------------------------------

Notes

[1] Interviewee 2.

[2] Gillmore, Dan, We the Media: Grassroots Journalism by the People, for the People. (Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media INC, 2006)

[3] Interviews were carried out in June and October 2013. Newsroom observations were carried out on a number of dates from June to October 2013 and throughout February 2014

[4] BBC Interviewee 1

[5] BBC Interviewee 5

[6] BBC interviewee 3.

[7] Allan, Stuart, Citizen Witnessing: Revisioning Journalism in Times of Crisis, (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2013).

[8] See Nip, Joyce Y.M. "Routinization of charisma: The institutionalization of public journalism online." Cited in Rosenbury, Jack and St John III, Burton (2010). Jack Rosenberry and Burton St. John, eds, Public Journalism 2.0: The Promise and Reality of a Citizen Engaged Press, (London, UK: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2009). Also Richard Sambrook, Are Foreign Correspondents Redundant? The Changing Face of International News. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2010).

[9] Wall, Melissa, Citizen Journalism: Valuable, Useless, Or Dangerous? (New York, NY: International Debate Education Association, 2012).

[10] Wardle, Claire, and Andrew Williams, UGC@thebbc: Understanding its impact upon contributors, noncontributors and BBC news, (Cardiff, UK: Cardiff School of Journalism).

[11] Harrison 2010.

[12] Jenkins, Henry, Convergence Culture–Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press.

[13] BBC interviewee 2.

[14] Interviewee 5.

[15] Hänska-Ahy & Shapour, "Who’s Reporting the Protests," Journalism Studies

[16] Interviewee 5.

[17] Interviewee 1.